60% of farmers continued to be outside the radar of govt extension services and without any access to modern technology

https://www.livemint.com/Politics/tfr5ONrNMoNvDctjI1AhdL/The-decade-that-failed-the-Indian-farmer.html

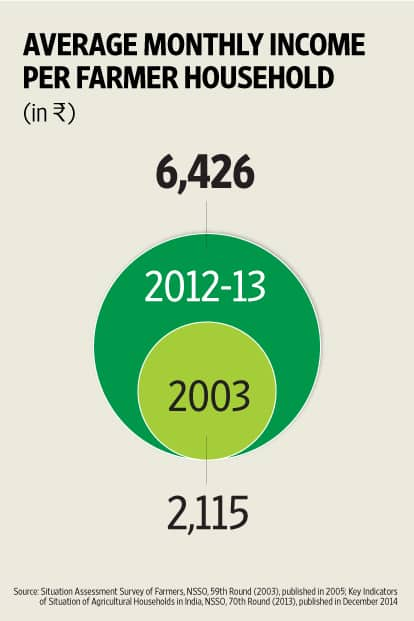

In the 10 years to 2013, the life of the average Indian farmer showed no improvement — it either stagnated or deteriorated.

That’s the conclusion that can be drawn by a comparison of the Key Indicators of Situation of Agricultural Households in India (2012-13), a survey recently released by the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO), with the first such report issued in 2003.

In that decade, land holdings became more fragmented—nearly 87% of families owned less than 2 hectares, while the proportion of rural households for which agriculture was the principal source of income increased from 34% to 37%. This could be due to a change in definition of the farmer household—the latest survey counts in families that did not possess or operate any land, provided they received more than ₹ 3000 from agricultural activities and had at least one member self-employed in agriculture either in the principal status or subsidiary status during the last year.

That’s the conclusion that can be drawn by a comparison of the Key Indicators of Situation of Agricultural Households in India (2012-13), a survey recently released by the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO), with the first such report issued in 2003.

In that decade, land holdings became more fragmented—nearly 87% of families owned less than 2 hectares, while the proportion of rural households for which agriculture was the principal source of income increased from 34% to 37%. This could be due to a change in definition of the farmer household—the latest survey counts in families that did not possess or operate any land, provided they received more than ₹ 3000 from agricultural activities and had at least one member self-employed in agriculture either in the principal status or subsidiary status during the last year.

While more farmer families are indebted (nearly 52%), the average outstanding loan per family shot up from ₹ 12,585 to ₹47,000. The share of non-institutional loans as a percentage of total advances decreased marginally; the moneylender is holding the fort. States infamous for farmer suicides are also where levels of indebtedness are the highest. In Andhra Pradesh, 93% of farming households were indebted; the average debt in the state was ₹ 1.23 lakh. In Telengana, carved out of Andhra Pradesh as a separate state in June, 89% of the households were indebted; their average debt was ₹ 93,500.

The income and expenditure data shows that many farming households continue to live a hand-to-mouth existence. In real terms, there has been hardly any increase in expenditure on productive assets. A big surprise here: the contribution of wages to incomes came down from 39% in 2003 to 32% in 2012-13, despite the introduction of the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, now in its ninth year.

Access to irrigation and government procurement at support prices remained stagnant over the decade. Sixty percent of Indian farmers continued to be outside the radar of government extension services and without any access to modern technology. Over 95% of paddy and wheat growers still do not insure their crops; only 10% of cotton growers insured theirs.

It’s a wonder then that agriculture (or perhaps the farmer) delivered a growth rate of 4.1% (in agriculture GDP) in the 11th Five-Year Plan (2007-2012).